Lytton, British Columbia

Lytton | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| The Corporation of the Village of Lytton[1] | |

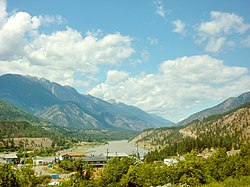

Lytton in 2011 | |

Location of Lytton in British Columbia | |

| Coordinates: 50°13′52″N 121°34′53″W / 50.23111°N 121.58139°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| Regional district | Thompson–Nicola |

| Incorporated | 1945 |

| Government | |

| • Governing body | Lytton Village Council |

| • Mayor | Denise O'Connor |

| Area | |

• Total | 6.54 km2 (2.53 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 195 m (640 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

• Total | 210 |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| Website | lytton.ca |

Lytton is a village of about 250 residents in southern British Columbia, Canada, on the east side of the Fraser River and primarily the south side of the Thompson River, where it flows southwesterly into the Fraser. The community includes the Village of Lytton and the surrounding community of the Lytton First Nation, whose name for the place is Camchin, also spelled Kumsheen ("river meeting").

During heat waves, Lytton is often the hottest spot in Canada despite its location north of 50°N in latitude. In three consecutive days of June 2021, it broke the all-time record for Canada's highest temperature, ending at 49.6 °C (121.3 °F) on June 29. This is the highest temperature ever recorded north of 45°N and higher than the all-time records for Europe and South America. The next day (June 30), a wildfire swept through the valley, destroying the majority of the town.

The Lytton area has been inhabited by the First Nations people for over 10,000 years.[2][3] It was one of the earliest locations settled by immigrants in the Southern Interior of British Columbia. The town was founded during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858–59, when it was known as "The Forks."

History

[edit]The people of the Nlakaʼpamux First Nation lived on the site before the town of Lytton was founded.[4] Lytton was on the route of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in 1858. The same year, it was named after Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the British Colonial Secretary and a novelist.[5] For many years, Lytton was a stop on major transportation routes, namely, the River Trail beginning in 1858, Cariboo Wagon Road in 1862, the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1880s, the Cariboo Highway in the 1920s, and the Trans Canada Highway in the 1950s. The town is much less important since the construction of the Coquihalla Highway in 1987, which uses a more direct route to the BC Interior.

In 2015, Lytton was featured on the CBC television show Still Standing with host Jonny Harris.[6]

2021 wildfire and destruction

[edit]

On June 30, 2021, the day after Lytton set a Canadian all-time high temperature record of 49.6 °C (121.3 °F), a wildfire swept through the community, destroying most structures.[7] All villagers were ordered to evacuate. Local MP Brad Vis said 90% of the village burned down.[8] Two people died.[9]

In the year since the fire, only a quarter of the properties were cleared of ash and debris. There was incessant wrangling between local residents who wanted to restore buildings and power immediately, and the local council who wanted fire-prevention standards in place. Coupled with inadequate insurance payouts and local record-breaking floods, residents were running out of time to restore the village. They were further hampered when another wildfire took out six residences across the river in July 2022.[10]

Name origin

[edit]Novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton was a friend and contemporary of Charles Dickens and was one of the pioneers of the historical novel, exemplified by his most popular work, The Last Days of Pompeii. He is best remembered today for the opening line to the novel Paul Clifford, which begins "It was a dark and stormy night..." and is considered by some to be the worst opening sentence in the English language.[11] Bulwer-Lytton is also responsible for sayings such as "The pen is mightier than the sword" from his play Richelieu. Though he was a popular author in the 19th century, fewer people today are aware of his prodigious body of literature, which spans many genres. In the 21st century, he may be better known as the namesake for the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest (BLFC), sponsored annually by the English Department at San Jose State University, which challenges entrants "to compose the opening sentence to the worst of all possible novels."

In 1858, Governor James Douglas named the town after Bulwer-Lytton "as a merited compliment and mark of respect." Bulwer-Lytton served as Colonial Secretary. As governor of the then-colony, Douglas would have reported to him.[12]: 158

Lord Lytton literary debate

[edit]On August 30, 2008, the Village of Lytton invited Henry Lytton Cobbold, the great-great-great-grandson of Edward Bulwer-Lytton, to defend the great man's honour by debating Professor Scott Rice, the sponsor of the BLFC, on the literary and political legacies of his great ancestor.[13] The debate received wide media coverage including The Globe and Mail, The New York Times, The Guardian, CBC's As It Happens, and many local and regional media outlets. The debate was moderated by Mike McArdell of Global TV. Lytton Cobbold provided a spirited and crowd-inspiring defence of his ancestor, and despite a factual and well-researched presentation by Rice, Lytton Cobbold emerged as the crowd favourite by a wide margin. In the end, Rice begrudgingly admitted to an admiration of Bulwer-Lytton. This event was held as part of the Village of Lytton's BC150 celebrations, which marked the 150th anniversary of the date that the community received its name, in addition to the province-wide celebration of the establishment of the original Colony of British Columbia on August 2, 1858.

Demographics

[edit]In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Lytton had a population of 210 living in 104 of its 118 total private dwellings, a change of -15.7% from its 2016 population of 249. With a land area of 6.73 km2 (2.60 sq mi), it had a population density of 31.2/km2 (80.8/sq mi) in 2021.[14]

Another 1,700 people in the immediate area live in rural areas and on reserves of the neighbouring six Nlaka'pamux communities.[which?]

802 members out of 1,970 registered members of the Lytton First Nation live on reserves immediately adjacent to the municipality.[15]

Climate

[edit]Lytton experiences an inland hot-summer mediterranean climate (Csa), using the -3 °C isotherm, or a dry-summer continental climate (Dsa), using the 0 °C isotherm. During summer heat waves, Lytton is often the hottest spot in Canada, despite its location north of 50°N in latitude. Because of the dry summer air and a relatively low elevation of 195 m (640 ft), summer afternoon shade temperatures frequently reach 35 °C (95 °F) and occasionally top 40 °C (104 °F). Lytton holds the record for the highest temperature ever recorded in Canada with a record high of 49.6 °C (121.3 °F) on June 29 of the 2021 Western North America heat wave.[16][17][18] This occurred after having already broken records multiple times during the previous days of that heat wave. This is the world's highest temperature ever recorded north of the 45th parallel. The previous record was 121 °F (49.4 °C) in Steele, North Dakota on July 6, 1936. Lytton has recorded a higher temperature than all but 4 U.S. states, with only Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Nevada ever recording higher temperatures. Lytton has also recorded higher temperatures than all of Europe and South America have ever recorded.[19][20][21]

Before the 2021 heat wave occurred, Lytton, along with the nearby community of Lillooet, shared the second-highest temperature ever recorded in Canada.[22] On July 16 and 17, 1941, the temperature reached a then-record 44.4 °C (111.9 °F) on both days in both communities.[23] The coldest temperature ever recorded in Lytton was −31.7 °C (−25.1 °F) on January 18, 1950.[24] While reporting on the new records in 2021, Global News noted that the official Environment and Climate Change Canada weather station is located in the shade and is about 1 °C (1.8 °F) cooler than the rest of the village.[25] Hot summer temperatures are made more tolerable by low humidity. The heat can be intense under usually clear skies and sunlight, or by the valley's radiant slopes. Forest fires are not uncommon during the summer.

Lytton's climate is also characterised by relatively short and mild winters (although average monthly temperatures in December and January are just below freezing), with Pacific maritime influence during the winter ensuring thick cloud cover much of the time. Cold snaps originating from arctic outflow occur from time to time, but tend to be short-lived, and mountains to the north usually block extreme cold from penetrating the Fraser Canyon.

Lytton receives 430.6 mm (16.95 in)[26] of annual precipitation on average, making it much drier than communities to the south but certainly wetter than some of the driest spots in the BC interior, such as Ashcroft, Kamloops, Spences Bridge, and Osoyoos. It has the driest summers in the interior of British Columbia and one of the driest summers of all places in Canada. Maximum precipitation occurs in the cooler months, with late autumn and early winter constituting the wettest time of the year.

| Climate data for Lytton WMO ID: 71765; coordinates 50°13′28″N 121°34′55″W / 50.22444°N 121.58194°W; elevation: 225 m (738 ft); 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1921–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 16.3 | 15.4 | 24.2 | 30.7 | 38.0 | 49.9 | 45.3 | 41.9 | 37.8 | 28.3 | 18.0 | 14.7 | 49.9 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

33.9 (93.0) |

40.4 (104.7) |

49.6 (121.3) |

44.4 (111.9) |

42.2 (108.0) |

39.6 (103.3) |

29.9 (85.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

49.6 (121.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

14.7 (58.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.1 (30.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.1 (24.6) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.8 (33.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.7 (−25.1) |

−25.0 (−13.0) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.1 (43.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−27.7 (−17.9) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−31.7 (−25.1) |

| Record low wind chill | −34.1 | −27.3 | −23.6 | −9.3 | −1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −9.8 | −28.1 | −36.7 | −36.7 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.7 (2.31) |

43.2 (1.70) |

31.2 (1.23) |

20.8 (0.82) |

20.6 (0.81) |

17.8 (0.70) |

18.7 (0.74) |

25.4 (1.00) |

29.0 (1.14) |

41.2 (1.62) |

60.3 (2.37) |

63.9 (2.52) |

430.6 (16.95) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 42.2 (1.66) |

34.7 (1.37) |

24.6 (0.97) |

20.8 (0.82) |

20.6 (0.81) |

17.8 (0.70) |

18.7 (0.74) |

25.4 (1.00) |

29.0 (1.14) |

40.0 (1.57) |

48.0 (1.89) |

41.6 (1.64) |

363.3 (14.30) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 19.4 (7.6) |

11.0 (4.3) |

6.2 (2.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.4 (0.6) |

12.8 (5.0) |

25.9 (10.2) |

76.6 (30.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 11.5 | 10.5 | 8.8 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 10.5 | 13.0 | 12.1 | 109.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 7.8 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 10.3 | 11.0 | 5.8 | 94.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 5.5 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 3.5 | 8.1 | 22.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1500 LST) | 73.1 | 58.0 | 48.1 | 37.5 | 34.6 | 36.4 | 31.5 | 31.2 | 38.7 | 55.8 | 72.2 | 75.7 | 49.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 56.0 | 81.6 | 143.0 | 186.7 | 224.2 | 243.8 | 265.2 | 244.2 | 182.0 | 121.8 | 55.7 | 48.1 | 1,852.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 21.1 | 28.8 | 38.9 | 45.2 | 46.9 | 49.8 | 53.7 | 54.4 | 47.9 | 36.4 | 20.5 | 19.1 | 38.6 |

| Source 1: Environment and Climate Change Canada[27] (rain/rain days, snow/snow days, precipitation/precipitation days and sun 1981–2010)[26][28][29][30][31][32] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: CBC (June record high only)[18] | |||||||||||||

Vegetation

[edit]Open coniferous forests of Douglas fir and ponderosa pine dominate the slopes around Lytton. Some black cottonwood is scattered among the conifers. Bunchgrass dominates the forest floor. Non-native trees cultivated in Lytton include black locust and Manitoba Maple.

Transportation

[edit]

Lytton lies on the Trans-Canada Highway as well as both the Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railways. The Canadian National Railway crosses both the Fraser and Thompson Rivers on two large steel bridges at Lytton. Via the Trans-Canada, Lytton is approximately 265 km (165 mi) from the city of Vancouver, 111 km (69 mi) north of Hope, and 84 km (52 mi) south of Cache Creek and Ashcroft.

Highway 12 runs north from Lytton 62 km (39 mi) to Lillooet, connecting there to Highway 99, which leads southwest to Pemberton and Whistler and beyond to Vancouver, and northeast to its terminus at Lower Hat Creek (Carquile) at a junction with Highway 97 just north of Cache Creek.

The Lytton Ferry, a free reaction ferry, crosses the Fraser River at Lytton. On the river's west side are Indian reserve communities of the Lytton First Nation and the Stein Valley Nlaka'pamux Heritage Park via trails from the confluence of the Stein River with the Fraser. From the ferry, a route known as the West Side Road leads through the Nesikep and Texas Creek areas to Lillooet and BC Highway 99; the route south from the ferry is much more difficult but leads to North Bend-Boston Bar. When the ferry is out of service because of ice or low water levels on the Fraser River, pedestrian access is available via a walkway on the Canadian National Railway bridge crossing the river.

Via Rail's Canadian and the Rocky Mountaineer pass through Lytton but do not make any stops. Via Rail's closest stops are Ashcroft, 80 km (50 mi) to the north, and North Bend/Boston Bar, 44 km (27 mi) to the south.

Municipal

[edit]The mayor of Lytton is Denise O'Connor, who was first elected in the 2022 municipal election.

Lytton is a corporate entity created under the Community Charter. Elections for Village Council are held every four years. The current Council comprises the following members:

- Mayor Denise O'Connor

- Councillor Nonie McCann

- Councillor Jessoa Lightfoot

- Councillor Melissa Michell

- Councillor Jen Thoss

Provincial

[edit]Originally part of the Lillooet provincial riding, then part of Yale-Lillooet, Lytton is now in the provincial riding of Fraser-Nicola, represented by Jackie Tegart of BC United, who first won in the 2013 election.

Federal

[edit]Federally, the town is in the riding of Mission—Matsqui—Fraser Canyon and is currently represented by Brad Vis of the Conservative Party of Canada, who was first elected in the 2019 elections.

Economy

[edit]The single main employer in the village produced forestry products and was forced to close because of market uncertainties in 2007.

Lytton is the self-proclaimed "River Rafting Capital of Canada" with Kumsheen Rafting Resort now the largest employer in the area. A provincial campsite, Skihist Provincial Park, adjacent to the Trans-Canada Highway six kilometres north of the village, has space for tenting as well as RVs and enjoys one of the few views available of Skihist Mountain, the highest summit of the Lillooet Ranges, across the Fraser to the west of Lytton. The privately run Jade Springs Restaurant, also east of the village on the Trans-Canada, burned down in the fire of June 2021.

Education

[edit]School District 74 operated Lytton Elementary School which was lost in 2021 Lytton Creek Wildfire.[33] and Kumsheen Secondary School (Kumsheen ShchEma-meet School).[34]

Stein Valley Nlakapamux School is a registered member with the B.C. First Nations Schools Association. The School is mandated to provide instruction and courses approved by the B.C. Ministry of Education and BC Independent Schools.

Notable residents

[edit]- Ilona Verley, Canadian-American drag queen[35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "British Columbia Regional Districts, Municipalities, Corporate Name, Date of Incorporation and Postal Address" (XLS). British Columbia Ministry of Communities, Sport and Cultural Development. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ "About Lytton". Village of Lytton. July 1, 2021. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Lytton was built on Kumsheen, and now the town is gone. In rebuilding, Nlaka’pamux people see an opportunity for reclamation Alex MMcKeen, The Star. July 17, 2021

- ^ "Lytton mayor says archeology slowing rebuild as residents protest delays". Global News. The Canadian Press. October 18, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- ^ Akrigg, Helen B. and Akrigg, G.P.V; 1001 British Columbia Place Names; Discovery Press, Vancouver 1969, 1970, 1973, p. 106

- ^ "Lytton hosts picnic with screening". Ashcroft Cache Creek Journal, Aug. 11, 2015

- ^ Lindsay, Bethany; Dickson, Courtney (June 30, 2021). "Village of Lytton, B.C., evacuated as mayor says 'the whole town is on fire'". CBC News. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Kotyk, Alyse (July 1, 2021). "Lytton fire: 90 per cent of B.C. village has burned in devastating blaze, local MP says". CTV News. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Kearney, Cathy (July 2, 2021). "B.C. man says he watched in horror as Lytton wildfire claimed the lives of his parents". CBC News. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Nia (August 5, 2022). "Canadian village razed by wildfire wrestles with climate-proofing its future". Reuters.

- ^ Petit, Zachary (January 18, 2013). "Famous First Lines Reveal How to Start a Novel". Literary Digest. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ Akrigg, G.P.V.; Akrigg, Helen B. (1986), British Columbia Place Names (3rd, 1997 ed.), Vancouver: UBC Press, ISBN 0-7748-0636-2

- ^ Alison Flood (August 19, 2008). "'Literary tragedy' of Bulwer-Lytton's dark and stormy night under debate". Guardian. Retrieved June 9, 2013.]

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), British Columbia". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ "Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Registered Population Detail". Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. Government of Canada. November 14, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Stuart, Riley; Gooch, Declan (January 13, 2017). "The NSW town where it gets so hot the roads melt". ABC News. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ @ECCCWeatherBC (June 29, 2021). "At 4:20pm, Lytton Climate Station reported 49.5°C, once again, breaking the daily and all-time temperature records for the third day running" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "B.C. town sets another all-time temperature record as 'prolonged, dangerous' heat wave continues". CBC News. June 28, 2021.

- ^ Samenow, Jason (June 30, 2021). "'Hard to comprehend': Experts react to record 121 degrees in Canada". Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Hopper, Tristin (July 2, 2021). "Literally hotter than the Sahara: How Western Canada became one of the hottest corners of the globe". National Post. Archived from the original on July 3, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "State of the Global Climate 2021 WMO Provisional report". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ "Hottest Places in Canada". Current Results Nexus. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ "Daily Data Report for July 1941". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Archived from the original on October 28, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ "January 1950". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "What is it like to live in the hottest place in Canada?". Global News. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "Lytton". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Climate ID: 1114741. Archived from the original (CSV (8222 KB)) on March 13, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ "Lytton British Columbia". Canadian Climate Normals 1991–2020. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Archived from the original on July 22, 2024. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Lytton (1921–1944)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. October 31, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Lytton (1944–1969)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. October 31, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Lytton (1970–1991)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. October 31, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Lytton (1994–2013)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. October 31, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Lytton RCS". Environment and Climate Change Canada. October 31, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "Home". Lytton Elementary School. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

270 - Seventh Street, PO Box 219, Lytton, BC, V0K 1Z0

- ^ "Home". Kumsheen Secondary School. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

PO Box 60, Lytton, BC, V0K 1Z0

- ^ "Ilona Verley on making HERstory as the first two-spirit and Indigenous contestant on Drag Race". GAY TIMES. August 14, 2020. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2023.