I Am Curious (Yellow)

| I Am Curious (Yellow) | |

|---|---|

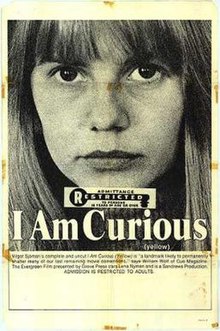

North American release poster | |

| Directed by | Vilgot Sjöman |

| Written by | Vilgot Sjöman (uncredited) |

| Produced by | Göran Lindgren (uncredited) Lena Malmsjö |

| Starring | Vilgot Sjöman Lena Nyman Börje Ahlstedt |

| Cinematography | Peter Wester (uncredited) |

| Edited by | Wic Kjellin (uncredited) |

| Music by | Bengt Ernryd (uncredited) |

| Distributed by | Grove Press |

Release date |

|

Running time | 122 minutes |

| Country | Sweden |

| Languages | Swedish English |

| Box office | $27.7 million (US/Sweden) |

I Am Curious (Yellow) (Swedish: Jag är nyfiken – en film i gult, lit. 'I Am Curious: A Film in Yellow') is a 1967 Swedish erotic drama film written and directed by Vilgot Sjöman, starring Sjöman and Lena Nyman. It is a companion film to 1968's I Am Curious (Blue); the two were initially intended to be one 3+1⁄2 hour film.[1]

Plot

[edit]Director Vilgot Sjöman plans to make a social film starring his lover (played by Lena Nyman), a young theatre student who has a strong interest in social issues.

Nyman's character, also named Lena, lives with her father in a small apartment in Stockholm and is driven by a burning passion for social justice and a need to understand the world, people and relationships. Her little room is filled with books, papers, and boxes full of clippings on topics such as "religion" and "men", and files on each of the 23 men with whom she has had sex. The walls are covered with pictures of concentration camps and a portrait of Francisco Franco, reminders of the crimes being perpetrated against humanity. She walks around Stockholm and interviews people about social classes in society, conscientious objection, gender equality, and the morality of vacationing in Franco's Spain. She and her friends also picket embassies and travel agencies. Lena's relationship with her father, who briefly went to Spain to fight Franco as part of the International Brigades, is problematic, and she is distressed by the fact that he returned from Spain for unknown reasons after only a short period.

Through her father Lena meets the slick Bill (Börje in the original Swedish), who works at a menswear shop and voted for the Rightist Party. They begin a love affair, but Lena soon finds out from her father that Bill has another woman, Marie, and a young daughter. Lena is furious that Bill has not been open with her, and goes to the country on a bicycle holiday. Alone in a cabin in the woods, she attempts an ascetic life-style, meditating, studying nonviolence and practicing yoga. Bill soon comes looking for her in his new car. She greets him with a shotgun, but they soon make love. Lena confronts Bill about Marie, and finds out about another of his lovers, Madeleine. They fight and Bill leaves. Lena has strange dreams, in which she ties two teams of soccer players – she notes that they number 23 – to a tree, shoots Bill and cuts his penis off. She also dreams of being taunted by passing drivers as she cycles down a road, until finally Martin Luther King Jr. drives up. She apologizes to him for not being strong enough to practice nonviolence.

Lena returns home, destroys her room, and goes to the car showroom where Bill works to tell him she has scabies. They are treated at a clinic, and then go their separate ways. As the embedded story of Lena and Bill begins to resolve, the film crew and director Sjöman are featured more. The relationship between Lena the actress and Bill the actor has become intimate during the production of Vilgot's film, and Vilgot is jealous and clashes with Bill. The film concludes with Lena returning Vilgot's keys as he meets with another young female theatre student.

Nonfictional content

[edit]The film includes an interview with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., filmed in March 1966, when King was visiting Stockholm along with Harry Belafonte with a view to starting a new initiative for Swedish support of African Americans.[2] The film also includes an interview with the Minister of Transportation, Olof Palme (later Prime Minister of Sweden), who talks about the existence of class structure in Swedish society (he was told it was for a documentary film), and footage of the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

Cast

[edit]

|

Uncredited roles[citation needed]

|

Release

[edit]

Censorship

[edit]The film includes numerous and frank scenes of nudity and staged sexual intercourse. One particularly controversial scene features Lena kissing her lover's (Borje's) flaccid penis. Released in Sweden in October 1967, it was released in the U.S. in March 1969, immediately attracting a ban in Massachusetts for being pornographic, with the Boston Police Department seizing the film reels from the Symphony Cinemas I & II on Huntington Avenue.[3][4] After proceedings in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts (Karalexis v. Byrne, 306 F. Supp. 1363 (D. Mass. 1969)), the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and the Supreme Court of the United States (Byrne v. Karalexis, 396 U.S. 976 (1969) and 401 U.S. 216 (1971)), the Second Circuit found the film not to be obscene.[5][4][6]

An arsonist set a fire in the Heights Theatre in Houston during the film's run there.[7] In April 1970, sheriff's deputies in Pensacola, Florida, seized prints of I Am Curious (Yellow), as well as Dracula (The Dirty Old Man), from the Ritz Theatre on N Tarragona St; the theater's manager was charged with "two counts of unlawful showing of an obscene film and maintaining a public nuisance".[8]

The film opened at the Vogue Art Theater in Denver, Colorado on 8 August 1969; hours after it opened there, it was seized by District Attorney Mike McKevitt, who promptly banned the film from being shown in the city, due to it violating a then-new obscenity law that was passed in the state; McKevitt had complained to District Judge Edward J. Byrne that the film was "obscene and pornographic".[9] The film's ban was challenged by its US importers, who succeeded in getting attorney Edward H. Sherman to return the film on 13 August 1969.[10] On 21 August 1969, Byrne labelled the ban an act of censorship and a "prior restraint on the defendants' right to freedom of speech"; subsequent to this, he lifted the ban on the film.[11] The film reopened at the Vogue Art on 22 August 1969, with 400 customers being reported as being in attendance.[12]

The film was censored by as much as 49 seconds in Australia between 1970 and 1971.[13] In the United Kingdom, John Trevelyan, a secretary of the British Board of Film Censors trimmed the film by eight minutes, reducing its running time to 114 minutes.[14][15]

Box office

[edit]The film was popular at the box office and was the 12th most popular film in the United States and Canada in 1969[16] and the highest-grossing foreign-language film in the United States and Canada of all-time[17] with a gross of $20,238,100.[18] It was number one at the US box office for two weeks in November 1969.[19] One reason it did so well was that it became popular among film stars to be seen going to the film. News of Johnny Carson seeing the film legitimized going to see it despite any misgivings about possible pornographic content.[20] Jacqueline Onassis went to see the movie, judo-felling an awaiting news photographer, Mel Finkelstein, alerted by the theatre manager, while leaving the theatre during the showing.[21][22][23]

Critical reception

[edit]Contemporary

[edit]Initial reception to Curious Yellow was divided. Vincent Canby of The New York Times referred to it as a "Good, serious movie about a society in transition",[24] and Norman Mailer said he felt "like a better man" after having seen it. Conversely, Rex Reed described the film as "about as good for you as drinking furniture polish" and Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times lambasted it as "a dog... a real dog" and "stupid and slow and uninteresting".[25] Rex Reed said the movie was "vile and disgusting" and Sjöman was "a very sick Swede with an overwhelming ego and a fondness for photographing pubic hair",[26] but Norman Mailer described it as "one of the most important pictures I have ever seen in my life".[27]

In the UK, Patrick Gibbs of The Daily Telegraph wrote that "there's not much for patrons in this cinema-verite material, presented in the Godard style as if it were holy writ."[28] Penelope Mortimer of The Observer wrote that "it is publicised as being very sexy. I have no more to say about it, except that that is a lie."[29] Alexander Walker of the Evening Standard remarked that as a result of having been cut in the UK, it "will now never satisfy the curiosity of people who know it as the first Swedish film to show the sex act. Every scene of that kind has been severely 'reduced' by our censor and we are left with a dull film of almost parochial impact about a girl public opinion-tester endlessly asking Swedes their views of class, colour, war and pacificism—oddly enough, not sex, unless you take a protest poster that reads 'COLOURED PEOPLE BE PREPARED—THE WHITES ARE STAGGERING' to fall into that category."[30]

Retrospective

[edit]In 1974, when an uncut version of the film debuted in Australia, critic Colin Bennett of The Age remarked that "almost the only fascination now lies in the revelation of what was considered far too notorious to be imported into [Australia] a few short years ago", adding that "sociologically, this satirical stuff may have had more point in 1967 Sweden, and I suppose it does reveal a modicum about Scandinavian social attitudes. It is also peculiarly dated. [...] One finds oneself no longer curious."[31]

In recent years, Yellow has received some reappraisal, thanks in part to Gary Giddins, who authored the 2003 essay accompanying the Criterion Collection DVD release, and a review by Nathan Southern on the All Movie Guide website. Southern assesses the picture as "a droll and sophisticated comedy about the emotional, political, social, and sexual liberation of a young woman... a real original that has suffered from public incomprehension since its release and is crying out for reassessment and rediscovery".[32]

As of August 2015, I Am Curious (Yellow) received a 52% rating based on 25 reviews, 13 "fresh" and 12 "rotten" on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.

Awards and honors

[edit]Nyman won the award for Best Actress at the 5th Guldbagge Awards for her role in this film and I Am Curious (Blue).[33]

In popular culture

[edit]Various television series have episodes with similar titles, such as Get Smart's series finale "I Am Curiously Yellow"; Moonlighting ("I Am Curious, Maddie"); The Simpsons ("I Am Furious (Yellow)"); That Girl ("I Am Curious Lemon"); Ed, Edd n Eddy ("I Am Curious Ed"); and The Partridge Family ("I Am Curious...Partridge").

In the Mad Men seventh season episode "The Strategy", Don Draper references having just seen this movie in a theatre.[34]

Episode 285 of This American Life featured a story called "I Am Curious, Jello," which followed up on the censorship trial between Los Angeles prosecutor Michael Guarino and Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra two decades after the case was thrown out of court.[35]

American car manufacturer Plymouth introduced a special order color for 1971. "Curious Yellow" is a vibrant greenish yellow, one of their "High-Impact" colors.[36]

The eleventh studio album by the English post-punk band The Fall makes reference to the film in its title, I Am Kurious Oranj.

References

[edit]- ^ Vilgot Sjöman, I Was Curious: Diary of the Making of a Film (Grove Press, 1968).

- ^ Sjöman, published scenario (New York: Grove Press, 1968, 264 p., 266 stills from the film; translated from the Swedish by Martin Minow and Jenny Bohman).

- ^ "Symphony Cinema I & II in Boston, MA". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ a b Whitebloom, Kenny (10 August 2011). "The Curious Case of 'I am Curious'". Boston TV News Digital Library. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "I Am Curious / Jag är nyfiken". Film International.

- ^ Björk, Ulf Jonas (2012). "Tricky Film: The Critical and Legal Reception of 'I Am Curious (Yellow)' in America". American Studies in Scandinavia. 44 (2): 113–134. doi:10.22439/asca.v44i2.4919. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Heights Theater History » Gallery M Squared". Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Coulter, Mike (7 April 1970). "After 2 Showings, Police Seize 'I Am Curious'". Pensacola News Journal. Pensacola, Florida. p. 2.

- ^ Wood, Richard (9 August 1969). "Controversial film banned in Denver". Rocky Mountain News. Denver, Colorado, United States. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Browne, Barbara; Wood, Richard (14 August 1969). "Seized Film's Distributors Challenge Colo.'s Obscenity Law". Rocky Mountain News. Denver, Colorado, United States. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Wood, Richard (22 August 1969). "Court Declares Swedish Film Ban 'Censorship, Restraint'". Rocky Mountain News. Denver, Colorado, United States. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Love, Ken (23 August 1969). "400 Jam Vogue Theater for Reopening of 'Curious'". Rocky Mountain News. Denver, Colorado, United States. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "Swedish Films". Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

December 1970 / Rated: SOA / Length: 8146 feet / Time: 90:31 / Censored by 00:22 / Reason: indecency / Comment: Reconstructed version. April 1971 / Rated: SOA / Length: 8000 feet / Time: 88:53 / Censored by 00:27 / Reason: indecency / Comment: Reconstructed version

- ^ "The Inside Page". Daily Mirror. London, England, United Kingdom. 13 March 1969. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "I Am Curious Yellow (1968)". bbfc.co.uk. British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1969". Variety. 7 January 1970. p. 15.

- ^ "Top Foreign Films in U.S.". Variety. 31 August 1992. p. 54.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (20 February 1995). "Top Grossing Independent Films". Variety. p. A84.

- ^ "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. 3 December 1969. p. 11.

- ^ Blood, Kirk L. (2016). My 1st Wife Had a Borderline Personality Disorder. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1-329-90421-7.

- ^ "She Was Furious" (PDF). San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco. 6 October 1969.

Jacqueline Onassis went to see the movie "I Am Curious (Yellow)"

- ^ Finkelstein, Mel (5 October 1969). "Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis walks out of Cinema Rendezvous theater on W. 57th St. after seeing "I Am Curious (Yellow)."". NY Daily News. Getty Images. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Sheehan, Susan (31 May 1970). "The Happy Jackie, The Sad Jackie, The Bad Jackie, The Good Jackie". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (11 March 1969). "Screen: 'I Am Curious (Yellow)' From Sweden". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "I Am Curious (Yellow) Movie Review (1969) – Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com.

- ^ Reed, Rex (23 March 1969). "'I Am Curious' (No)". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "Vigot Sjöman". The Daily Telegraph. 21 April 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

Norman Mailer announced that it was "one of the most important pictures I have ever seen in my life"; but the film critic Rex Reed called it "vile and disgusting" and described Sjöman as "a very sick Swede with an overwhelming ego and a fondness for photographing pubic hair"... When the Supreme Court finally allowed the film to be released, it benefited considerably from the publicity. But cinema-goers seeking titillation were generally disappointed. The sex scenes were more surprising than erotic and were dominated by the rather vague narrative in which the actors (Lena Nyman, Borje Ahlstedt and Sjöman himself) all played characters with their own names. But it marked a turning point for censorship, and by the 1970s a naked woman or a bare male bottom in a mainstream film barely raised an eyebrow.

- ^ Gibbs, Patrick (7 March 1969). "Legend without the spell". The Daily Telegraph. London, England, United Kingdom. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Mortimer, Penelope (9 March 1969). "Isadora reborn". The Observer. London, England, United Kingdom. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Walker, Alexander (6 March 1969). "Sex again—with no bite". Evening Standard. London, England, United Kingdom. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Bennett, Colin (8 February 1974). "No longer so curious in Australia 1974". The Age. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "I Am Curious (Yellow) (1967) – Vilgot Sjöman – Review – AllMovie". AllMovie.

- ^ "Lena Nyman". Swedish Film Institute. 1 March 2014.

- ^ Sepinwall, Alan (19 May 2014). "Review: 'Mad Men' – 'The Strategy': Regrets, I've had a few". Hitfix: What's Alan Watching?.

- ^ Segal, David (25 March 2005). "Know Your Enemy". This American Life. No. 285. Chicago: WBEZ. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Car paint colors, Car colors, Mopar".

External links

[edit]- I Am Curious (Yellow) at IMDb

- I Am Curious (Yellow) at Rotten Tomatoes

- Still Curious an essay by Gary Giddins at the Criterion Collection

- Byrne v. Karalexis

- 1967 films

- 1960s avant-garde and experimental films

- 1967 drama films

- Swedish avant-garde and experimental films

- 1960s erotic drama films

- 1960s Swedish-language films

- Films directed by Vilgot Sjöman

- Films about adultery

- Swedish black-and-white films

- Films about sexually transmitted diseases

- Films about filmmaking

- Films about Martin Luther King Jr.

- Films set in Stockholm

- Films shot in Sweden

- Censored films

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Self-reflexive films

- Sexual revolution

- Works subject to a lawsuit

- Swedish erotic drama films

- Film censorship in the United States

- Film censorship in Sweden

- 1960s Swedish films